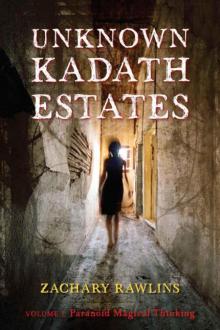

Paranoid Magical Thinking (Unknown Kadath Estates)

The Unknown Kadath Estates Books

The Night Market

Paranoid Magical Thinking

The Mysteries of Holly Diem (2013)

The Floating Bridge (2014)

Other Books by the Same Author

The Central Series:

The Academy

The Anathema

The Far Shores (2013)

For Mr. Sleep, my partner in crime.

Copyright © 2012 by Zachary Rawlins

Cover photograph copyright © Özgür Donmaz

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

Published by ROUS Industries.

Oakland, California

spook_nine@yahoo.com

978-0-9837501-1-6

Cover design by Dahlia & Poppy Design

First Edition

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. No Fixed Position. 6

2. Rain Fade. 25

3. Lotus Effect. 47

4. The Tenant. 59

5. Tropospheric Scatter. 79

6. The Girl Who Never Came Home. 98

7. Ghosting. 111

8. Anti-Life Equation. 132

9. Bad Houses. 147

10. Some Girls Wander by Mistake. 162

11. Displacement of a Fixed Volume. 177

12. A Fully Functional Model of the Human Heart. 184

13. Neurasthenia. 195

Epilogue. 207

1. No Fixed Position

All relationships are inherently unstable. My relationship with the truth is no exception. Something to consider.

The strange thing about the city – or, rather, the first strange thing – I have no memory of the highways that brought us there.

That may not sound unusual, but for me, it is quite abnormal. I have always had an almost perfect map of my surroundings in my head. I can remember every turn we took in the proceeding fugitive weeks; running when we had to, hiding where we could, always moving. We travelled on back roads and forgotten highways; a long crawl across miles of desolate land, a parade of decaying motor courts and half-dim neon signs. I remember crossing granite mountains, traces of dirty grey snow on the side of the road, then a vast desert, gravel and scrub brush withering under unbridled sun. It reminded me of the surface of the moon, or the desolation of the ocean floor. I do not, however, remember the drive into the city.

I knew I had arranged an apartment, because I had a letter with a key and a map from the landlady, though I had no idea how I had obtained them. I did not let that worry me. There was no advantage in worrying.

What I do remember is the first time I saw the city, because I never forget my dreams. Asleep, I had walked patchwork streets of concrete and cobblestone, damp with early morning rain, hydrocarbon rainbows stretched across the puddles. The towers of downtown met the sky jagged as broken teeth, fractured on bitter grey clouds that hung over the city like vultures waiting for a death that was always imminent. The oldest buildings were carved from a grey-green stone that I had never seen before, smooth as glass to the touch, but with an internal coldness that burned the tips of my fingers.

It bothers me that I cannot remember waking from this dream.

When we first arrived, the city gave me an awful sense of déjà-vu, like waking from a dream of losing teeth to find my mouth empty. The city brooded at the end of a gelded river, dammed upstream to provide drinking water for the uncounted millions who lived there. The oldest neighborhoods brushed against the rocky coast and the placid, dark waters of the ocean, wooden skeletons exposed to the vicissitudes of time and tide. The freeway ran through the western side of the city, beside a small enclave of modern conveniences and contemporary high-rises. The buildings everywhere else were ornate and crumbling, often built from the strange green stone, as covered with cornices and gargoyles as they were with satellite dishes and outflow vents for climate control systems. The remains of a river, now confined to a garbage-choked concrete canal, bisected the city neatly. From my seat in the van, I could not see anything on the near side of the river that appeared less than a century old. Along the rocky coastline beyond the river, things were even more ancient and rundown.

The city was grotesque and magnificent, ornate and forgotten architectural styles cheek-and-jowl with scenes of tremendous decay. One building we passed was crawling with strange statues, fish-men and octopus-faced things, every window broken, not a single light inside. Another was wrapped in suffocating layers of vines with bizarre, garish purple blooms. The faces I saw behind the dirty glass windows were blank and uncaring. An ancient colonial house slowly merged with the earth, wood turned the non-color of time and exposure, swallowed by the shadow of the squat brick foundry across the street.

The map I had been given was detailed, but not particularly helpful. The layout of the city was bewildering, ancient streets meandering around forgotten landmarks and tiny stone alleys spiraling out in all directions. I followed the map as closely as possible, but one-way streets and a shortage of signs made it hard for me to be sure that I knew where we were going.

We found our apartment building in the heart of the emptiest neighborhood I had ever seen in my life, blocks of vacant, decaying buildings surrounding roads that were crumbling from neglect.

Of course, once we finally found the place, we had to drive back to the nearest public transit, following the elevated train tracks until we came to a nearby station – to be certain we weren’t followed. We left the van on a side street two blocks from the station. April fell soundly asleep with her head resting on my shoulder, soothed by the labors of the train as it lumbered back to our new home, the Kadath Estates on Leng Street, in a district by the same name.

We could see Leng Street from the parking lot of the train station, running straight through the heart of a desolate residential area, the neighborhood built in a depression, on what had probably been marshland at some distant point in the past. A staircase was cut in the trash-strewn slope that descended down into our new neighborhood, hundreds of steps hewn from slippery black stone. The path was cool in the shadow of fragrant and towering pines, remnants of a forest that had crowded the hillside long before the city had swollen to fill all but the steepest places.

Our neighborhood had been abandoned sometime before, whether in response to a disaster or in anticipation of renovations that never arrived, I could not be certain. Leng Street was a large commercial boulevard, desolate except for the leaves and plastics bags creeping down the expanse of worn asphalt, moving along with a breeze that brought the scent of the polluted ocean. April stayed closer than usual and I was glad for it.

The Kadath Estates hardly seemed to merit the grandeur of its name, though it was inarguably old. The building was roughly square in shape and wedged between crumbling tenements. The dirty brown river crawled through a concrete embankment immediately behind it. Dusty green ivy burdened with fragrant purple flowers blanketed the walls of the lower story. The second and third floors groaned under the weight of stone flourishes fashioned into fantastic and horrible creatures, buttresses and clusters of statues that reminded me vaguely of hounds. If I am any judge, the Kadath Estates were a hundred years older than any other building on the street, though in slightly better repair. Like the ol

dest parts of the city, the Estates were composed mainly of blocks of slick, green-speckled stone. The door was heavy and reinforced with wrought iron, the kind of door intended to keep out people who were serious about getting in.

I was glad the manager had sent a key, because I did not see a callbox or a manager’s office. The lock was almost as old as the building itself; the key was a heavy, ornate thing that looked like, but could not possibly have been tarnished silver.

The gate swung closed behind us with a squeal that spoke of years of accumulated rust and neglect. I caught the reflection of a cat’s flat eyes in the shadows of the foyer before it disappeared into up into the darkness of the stairwell. The hall was cold and drafty, the stone steps of the stairs partly overgrown with a faint blue moss. Bundles of telecommunication and power cables were attached to the walls with metal staples, branching chaotically and punching haphazardly through the stone. External lights were placed sporadically throughout the stairwell, providing flickering, minimal illumination. Water dripped from every surface and the smell of mildew was pervasive.

I walked up the stairs slowly so April would not lose hold of the back of my jacket. Normally I would have held her hand, but I was worried about what we might find waiting for us at the top, and I wanted my hands ready. There was nothing waiting for us on the second floor hallway besides the resentful black cat, though, so we went to the unit marked 2A and used the reassuringly mundane door key that the manager had sent.

The door took some persuading to open, warped by the damp. The living room was empty, with new roll carpet and bundles of cable jutting from a rough breach in the wall. It smelled mostly of fresh paint and cleaning solution, and just a little like the wet stone hidden behind an inch of drywall. It was actually jarring how normal the inside of the room was, in comparison to its bizarre exterior. We made a quick circuit of the apartment – one bedroom, furnished with a bed and a bureau, as agreed. One bathroom with a bathtub, a shower curtain, a medicine cabinet behind the mirror. One kitchen with an electric stove, as required. A noisy refrigerator with nothing inside but a lingering smell of garlic.

Catching April’s eye, I nodded toward the bedroom, pulling a screwdriver from one of the pockets in my jacket. She took a smaller tool her backpack and we set about disassembling the bed frame, the bureau, the medicine cabinet – anything that could be pried apart. The blinds were shaken out and inspected, the mattress turned over and then thoroughly jumped on by April. I stuck my head underneath the sink in the bathroom and the kitchen, using a flashlight to scope out the recessed areas behind the pipes. I inspected the toilet, the tank and the mounting. We took the covers off every vent and power outlet in the apartment, the grill from the refrigerator, and knocked on the walls. I am not sure why we knocked on the walls, but we always did. Then we pulled the carpet up in every room to inspect the floorboards.

“Looks okay.”

We sat in the middle of the living room. I felt bad for April – she looked spent, her brown hair damp with sweat, and we weren’t even half done. She still had to make the place safe for herself.

“Do you want chicken for dinner?”

April thought about it for a little while, then nodded reluctantly.

“Then you’d better get started,” I urged. “Because the restaurant is back by the station, and you don’t want to walk with me.”

April dithered a moment longer, her thin fingers digging unconsciously into the fabric of the carpet, but hunger won out over exhaustion. She returned to the bedroom and started unpacking her gear. I followed and lay on the floor to watch April do her thing. I had seen it many times before, but that didn’t make it less fascinating.

She started by putting brand-new sheets on the bed, along with new pillows, both taken from her enormous backpack. She aligned the pillows carefully, followed by her own possessions, lining them up as neat as a row of ducklings behind the bulk of her backpack, right down the middle of the comforter. April likes stuffed animals, the bigger the better. She doesn’t seem to mind if they are ugly, so she doted on each piece of her collection, arranging them with thoughtful precision.

April walked the perimeter of the bedroom three times on her wobbly legs, fingers trailing along the wall for balance, her other arm extended as if she were on a tight rope. Her fingertips lingered over every flaw and facet of the wall. April returned to her bag and got a hammer, nails, and the sheets of paper that she had fabricated during the drive.

If there is a pattern, a method to the way April builds her barricades, then I have never been able to see it. Of course, April sees any number of things that I never will. The symbols were painstakingly drawn on coarse white sketching paper in heavy-handed charcoal pencil. Or, perhaps draw is the wrong word.

The pages were neatly inscribed with symbols, letters from a language that April invented, which only she understood. She has tried to explain the concept behind it, but most of what she says is beyond me. As best as I can understand, April’s language eliminated the concept of representation. Instead, she uses a separate word for each specific thing, with mutable elements that describe place in time and relationship with the observer. There were no ‘cars’, or ‘red cars’, or even ‘red cars with ridiculous spoilers’. Rather, a single word meant ‘that specific red car with a ridiculous spoiler that drove by us a moment ago’. A unique word that was used once and then never again.

The letters she drew looked like cuneiform, pictographs, hieroglyphs, Japanese wood-block prints. Together they spelled out protection, security and anonymity; a wall that kept the world and April apart. I could not have told you what each individual piece meant, but you would have been blind not to see meaning in the whole.

Her alphabet was beautiful and unsettling, reoccurring in my dreams as enigmatic as ciphers. I was grateful, somehow, that I couldn’t read them. Even a basic understanding of April’s private language had disquieting implications.

The creation of spontaneous savants is not unprecedented. Twins develop private languages as infants, forgetting them later in life. A man beaten until his brain swelled in his head saw nothing but fractals when he recovered, the only person in history capable of drawing the impossibly intricate figures by hand. Another man had no appetite for number until he suffered repeated lightening strikes and became something of a human calculator.

The brain responds to damage in surprising ways.

Of course, all of those were accidents of nature or circumstance. April’s remarkable and deviant genius was the result of deliberate tampering with her mind and development.

April stumbled back to the center of the room almost an hour later, folding up neatly on the floor beside me, face creased with exhaustion. I held her briefly and patted her head, then set her down carefully on the bed, where she curled up with her bizarre plush menagerie.

“Are we going to be able to stay here for a while, Preston?”

April yawned dramatically, stretching out to accommodate the gesture, her tangled bangs damp with sweat against her forehead.

“You tell me. Did you make it safe?”

April’s nod was grave. She knew as well as I did that safe was both relative and temporary. And she wasn’t done. Not unless April planned to spend the rest of her life in the bedroom.

“Then we are safe,” I shrugged. “Finish the bathroom and then stop for the night, okay? The rest can wait.”

She yawned again, her movements exaggerated and played for sympathy. Our last landlady had confused April with some long-dead grandchild and dressed her like a doll, all bows and ribbons and velveteen dresses. She would stand out until I could get her some normal clothes.

“You’re still hungry, right?”

It was not an idle question. April’s eating habits were unpredictable at best. Sometimes she lost interest in food. Sometimes for days. Other times, when I wasn’t paying attention, she would make herself sick on breakfast cereal or canned fruit.

“Yeah. A soda, too. Alright?”

“Okay,” I said, dragging out my cell to check and see if caffeine was allowable. “But you have to promise to sleep tonight. We have a bunch of stuff to do tomorrow.”

“I promise,” April said, nodding her head solemnly. “But you promise, too, Preston. No arguing about sleeping on the floor tonight. That bed is big enough for both of us.”

“We’ll see,” I lied. “You want mashed potatoes?”

“You know I do,” April huffed, pulling her charcoal pencils from her oversized backpack.

That was my cue, and I was hungry myself, so I headed out the front door. I was so busy searching the many pockets of my jacket for headphones that I almost walked over the shorthaired lady with glasses who stood in the hallway.

“Ahem.”

“Oh, hello!”